Is South Africa's trade policy failing the agricultural sector?

Introduction

An export-led strategy underpins South Africa's trade policy, which entails a deliberate effort to get the country's agriculture and other industrial sectors to export products beyond existing international markets. There are at least two diametrically opposing views around how well South Africa has executed this strategy in agriculture.

Diverging trade policy views

The first view is that South Africa has not done enough to open up new markets, limiting the country's scope to further grow agricultural exports. This view is widely shared by private-sector roleplayers who have struggled to penetrate and expand market share in key growing countries such as China, India, and Saudi Arabia. Private-sector roleplayers argue that,over the past few years the growth in South Africa's agricultural exports in these key markets has primarily been driven by productivity gains that have established a big enough competitive advantage that overcomes high tariff and non-tariff barriers.

Experiences from exporters reveal that government has a lack of institutional and human capacity to deliver critical services such as testing laboratories for perishable products such as meat, which has led to delays in the issuance of export permits. Another example includes protracted government negotiations that took over a decade to conclude to allow citrus producers in certain parts of South Africa access to the US market. There were also the costly regulations imposed on South African producers to align with unjustified citrus black spot (CBS) requirements, which continue to cost the industry. South African government's lack of appetite to pursue a free trade agreement with the United States post-2025 after the expiry of AGOA is also worth noting. Based on these issues, a microcosm of those around fundamental state capacity, the prevailing sentiment is that South African agricultural exports have increased despite the limitations in market access and a general lack of sufficient support from the government.

The second view is that South Africa has excelled in opening up new markets, as evidenced by several free trade agreements (FTAs) with critical regional and international markets. This includes the:

- a) Southern African Development Community (SADC) FTA,

- b) SADC-European Union (EU) Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA),

- c) SACU/Mozambique-United Kingdom (UK) EPA,

- d) The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA),

- e) SACU-MERCOSUR[1] Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA)

All the above have been concluded over the past 15 years, which is quite a considerable feat in itself, given the technical and institutional demands that have to be committed to negotiating and successfully implementing trade agreements. Ironically, though, these FTAs are in only two of South Africa's biggest markets – Africa and Europe – which collectively account for 65% of the country's total agricultural exports in 2020. The SACU-MERCOSUR preferential trade agreement (PTA) is a narrowly focused and low-ambition trade arrangement and has not had a large impact. It is thus entirely plausible to argue that the opening of markets through these agreements has indeed deepened, consolidated and improved South Africa's position in the EU and Africa – particularly the latter, where pervasive challenges of non-tariff barriers remain a critical problem.

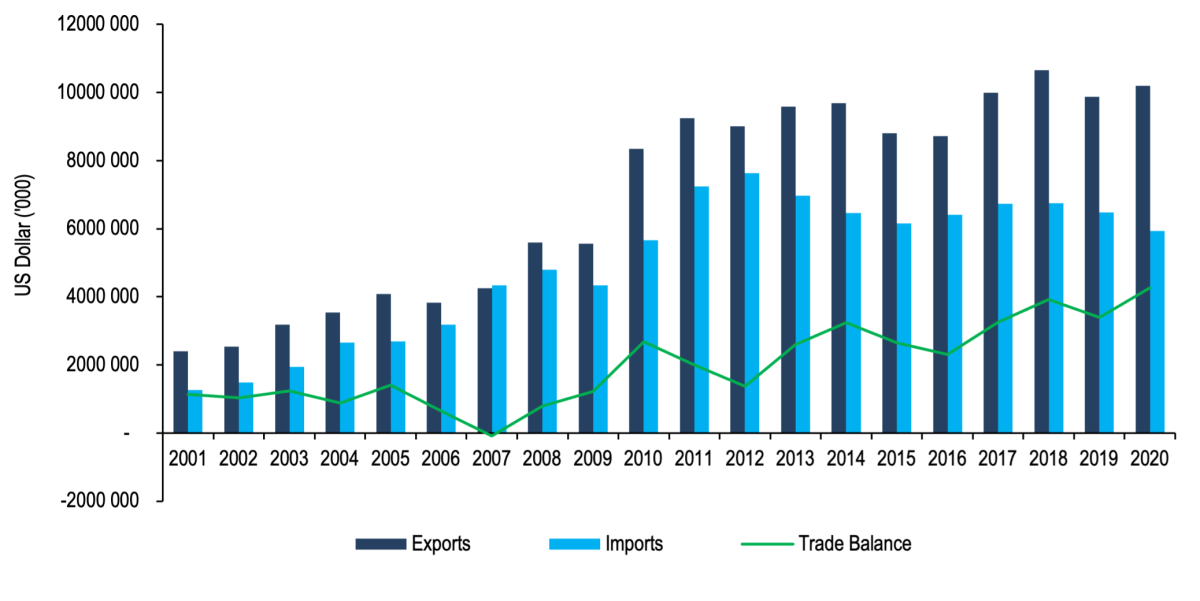

Table 1: South Africa's agricultural trade

Source: Trade Map (2021) and Authors calculations

However, it is equally plausible to argue that South Africa would be best served if its market access were to be diversified beyond Africa and Europe, an argument at the core of the country's export-led strategy. The Middle East, Far East (Asia), North and South America currently account for 35% of South Africa's agricultural exports. This is perhaps where most of the attention and pursuit of FTAs would be more critical. Some of South Africa's fiercest competition is from "Global South" producers such as Chile, Peru, Australia, Argentina, New Zealand, and Uruguay. They have struck various forms of trade agreements with third markets in Asia, the Middle East ,and the Americas. Table 2 below compares South Africa and its competition in Asia – South Africa only has the SACU India preferential trade agreement (PTA), which is yet to be finalized after 15 years of negotiations.

Meanwhile, Peru and Chile have preferential market access in all of the listed markets. In contrast, Argentina, New Zealand, and Australia have a pact with the ASEAN regional block and a bilateral with China. It effectively means that South Africa is facing higher tariffs against the key competition – and local producers have to overcome these tariffs primarily through farm-level technical efficiency.

Table 2: Comparing market access between South Africa and its competitors in Asia

Source: Meyer (2019) and Authors' updates

* Agreement that is yet to be finalized.

NB: SACU: Southern African Customs Union; GSTP: Global System of Trade Preferences among developing countries; PTN: Protocol on Trade Negotiation

From Table 2, it is clear that South Africa is lagging in fostering market access in regions such as Asia, which represents a frontier of expansion. The question is, can South Africa realistically follow the model of its competitors in aggressively pushing for more access in third markets? South Africa is an industrializing economy with a unique set of challenges. Many feel that trade liberalization has severely limited South Africa's capacity to address structural inequality, and there is a political hesitancy to open up markets beyond current levels.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, there has clearly been a desire to retain trade policy space, but this is likely to limit the ability of the country to pursue further FTAs, given the need to make concessions that further liberalize markets. This explains the reluctance of South Africa to pursue a SACU-US FTA, or a bilateral with China, and the stalemate of the SACU-India PTA. Moreover, the focus on localization means South Africa's inward risks are becoming protectionist, further complicating our efforts to expand market access for agricultural commodities and various agro-processing products the country produces.

This leaves South Africa with an extremely narrow set of options that balance political and economic imperatives. In essence, South Africa may not readily enter into additional FTAs beyond those with the EU, UK, and Africa. Rather, the country will likely target low-ambition trade agreements with specific countries, primarily Preferential Trade Agreements, which focus on liberalizing a specific set of commodities and agro-processed products. There is very little chance of South Africa embarking on deep and extensive tariff cuts on goods and services, especially given that the costs of opening up markets cannot be determined with certainty. With that said, it would be unfair to argue that South Africa's trade policy has been regressive, and suggestions that the government has done little to boost agricultural exports are inaccurate.

From now on, policy discussions of the Agriculture and Agro-processing Master Plan[2], which aims to boost exports and expand markets in the Middle and the Far East, will focus on unlocking technical barriers to trade (TBTs) and establishing sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) protocols.

References

Meyer, F., 2019. Is there room for growth in South Africa's agriculture? Paarl: Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa.

Trade Map, 2021. Agricultural trade data, Geneva: International Trade Centre. TradeMap

[1] The Southern Common Market (i.e. Mercado Común del Sur) is the a trade bloc of South American countries, which include Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

[2] The Agriculture and Agro-processing Mater Plan is social compact initiative for advancing inclusive growth in South Africa’s agricultural sector. By the time of writing, the expectations are that the Plan will be launched towards the end of 2021, as the process is currently at final stages of consultations between the business community, government, and labor, amongst other social partners. The Master Plan essentially follows the approach of Chapter six of the National Development Plan.

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.