Why South African agricultural products face frontiers in African markets

Introduction

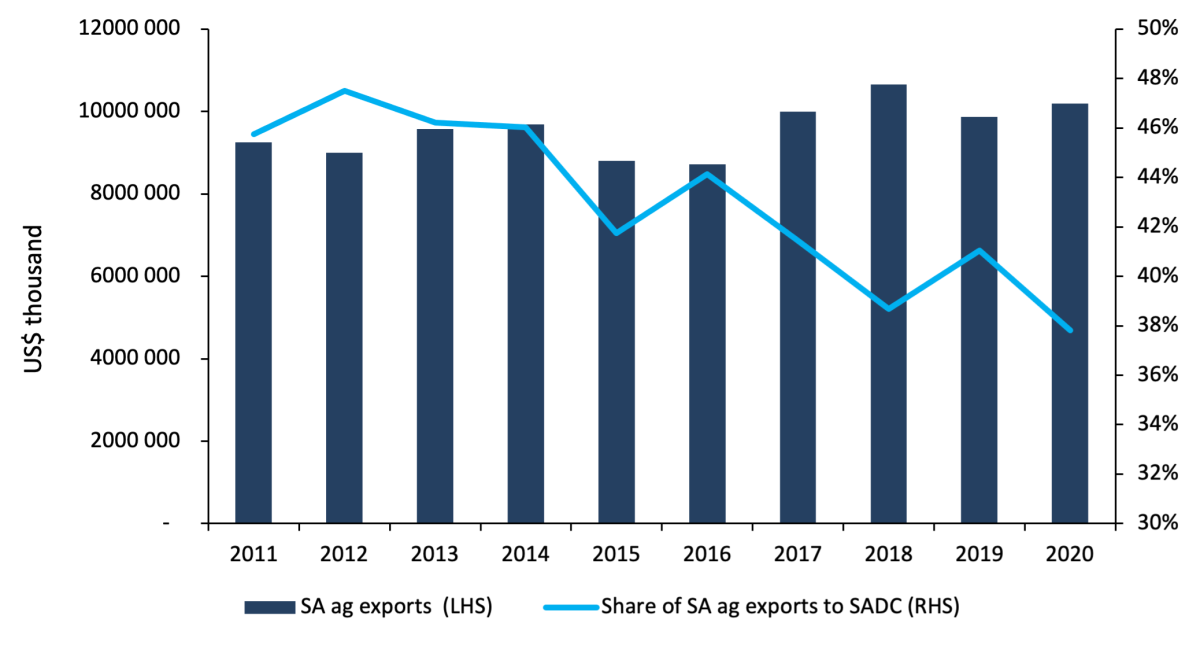

There have been hopes that the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) may provide opportunities to expand South Africa's agricultural exports into the African continent.[1] This comes against the backdrop of Africa being the largest market for South Africa's agricultural sector - accounting for an average of 43% (or US$4,1 billion) a year of all agriculture exports over the past decade (see Figure 1). But how much more potential can South Africa unlock in the African market? In this article, we argue that the benefits of the AfCFTA are not as significant as previously thought due to structural limitations preventing the agricultural sector from expanding its exports into untapped markets.

Trade dynamics

Most of South Africa's agricultural exports into the African continent (89%) are concentrated within the Southern Africa Customs Union (SACU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Free Trade Area (FTA). However, the product scope of exports into SACU and SADC is quite diverse and includes maize, processed food products, apples and pears, sugar, animal feed products, prepared or bottled water, fruit juices, and wine. With 90 cents of every Rand in agricultural exports earned within SACU/SADC, it is important to diversify export markets beyond the region. The question is, just how much more can South Africa export beyond SACU/SADC? The most reasonable assumption is for South Africa to target West, East, and North Africa.

But such an expansion has limits. For a start, Africa north of the Saharan, more specifically the Maghreb region (i.e., Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia), is much closer to Europe, and its trade activity is more closely linked to the EU rather than sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, South Africa competes with this region in several products where it aims to increase its exports, primarily the high-value horticulture products. Establishing a market presence in North Africa may prove challenging due to direct competition with well-established EU supply chains and competitive local produce.

South Africa's realistic opportunity within the African continent is more likely in East and West Africa. Leveraging the AfCFTA's tariff-free movement of goods would potentially boost the country's agricultural exports to these regions. But, at least in the near-term, trade with these regions may not yield many benefits for South Africa. There are at least three reasons why not: East and West African regions have a range of Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs), which could hinder boosting trade regardless of lower tariffs brought by the AfCFTA; secondly, high levels of corruption, which increase the costs of doing business, have proven to be a major concern for business in South Africa[2]; and thirdly, fragmented value chains owing to poor connectivity and infrastructure are also a major contributor to transport costs, which tend to increase significantly as goods are transported inland.

This narrow scope of expanding agricultural exports in the African continent typically leads to frustration amongst business leaders, who continue to see improvement in production domestically, but are limited in avenues for sales. The major economies in the east and west of the continent, Nigeria and Kenya, remain very small markets for South Africa's agricultural exports, each accounting for a mere 2% a year. Still, Nigeria spends over US$6 billion on agricultural imports a year, despite its new policy of reducing food imports. The key beneficiaries of the Nigerian agriculture market are Brazil, the US, China, Russia, Canada, New Zealand, and Germany. This is through imports of wheat, dairy products, sugar, processed food, palm oil, and maize, amongst other products.

Meanwhile, Kenya is a relatively small market with just over US$2 billion worth of agriculture and food imports a year. The key suppliers are Indonesia, Malaysia, Argentina, Russia, Pakistan, Uganda, Tanzania, India, and Egypt. Kenya’s key agriculture and food imports are palm oil, wheat, rice, sugar, processed food, maize, dairy products, pasta, and sorghum, amongst others.

The composition of food and agricultural imports into these two countries is also indicative that South Africa's scope to export high-value horticulture, meat, and wine products is limited. These countries import primarily staple food products, and as such they are markets that would be worth pursuing for grain farmers. Still, non-tariff barriers remain a stumbling block, even for grains, as Kenya prohibits importing and growing genetically modified (GM) maize. This is a significant hindrance for South Africa, as roughly 80% of maize grown in the country is genetically modified.[3]

Figure 1: South Africa's agricultural exports and share of it to the SADC region

Source: Trade Map and Authors' updates

Conclusion

It’s evident that South Africa's agriculture export opportunities will be limited in general and most likely be opportunistic and focused on specific commodities or products in the short to medium term. For instance, South Africa's maize exports have been relatively high during drought periods in East Africa and under special circumstances that require short-term contingency policy measures to allow for GM maize exports. Beyond maize, the approach will have to be more deliberate. For example, South Africa will have to consider a shift towards exports of processed food products.

Trade Map[4] shows that Africa's imports of processed food products grew by 25% between 2018 and 2020, which is an opportunity for South Africa to explore. The sector will have to develop markets for processed food in East and West Africa, which represents the remaining frontier to grow the African market beyond current levels. From a policy perspective, the South African government may need to revise the Africa Strategy and establish task teams that can facilitate and broker market access for agribusinesses that seek to establish a market presence and investments in these key regions.

References

Transparency International, 2021. Sub-Saharan Africa's Corruption Perception Index Results. Berlin: Transparency International.

Morokong, T., Pienaar, L., and Sihlobo, W., 2021. New opportunities for South African agriculture: the African Continental Free Trade Area. Cape Town: Econ3x3.

Sihlobo, W., 2021. Africa is not a good maize export market right now - here's why. Cape Town: News24

Trade Map, 2021. Agricultural trade data, Geneva: International Trade Centre.

[2] Transparency International, 2021

[4] The proper labeling of this category in the Trade Map data is “HS code: 2106”, “Food preparations, n.e.s.”

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.