Creating jobs, reducing poverty II: The substantial employment performance of the informal sector

Preamble

This is the second in a short series of edited extracts from a new REDI3x3 book: The South African Informal Sector: Creating Jobs, Reducing Poverty. The research findings reported in the book address a significant knowledge gap in economic research and policy analysis.

The book flags the importance of explicitly addressing the informal sector in policy initiatives to boost employment and inclusive growth and reduce poverty. Its last chapter – from which the extracts are drawn – generates a synthesis of key findings on the informal sector and develops the outlines of a proposed policy approach.

This extract considers the job-creation performance and potential of the South African informal sector. Forthcoming articles will address the barriers and constraints faced by informal enterprises and workers; a proposed policy approach to strengthen the informal sector and boost its role in job creation, poverty reduction and livelihoods; and a constructive way to approach the possible ‘formalisation’[1] of the informal sector.

* More information on the book is provided at the end of this article

Introduction

The previous article discussed the size and impact of the South African informal sector, also distinguishing key policy-relevant features. Approximately 2.3 million people worked in the non-agricultural informal sector in 2013. (In 2018 it has reached 2.9 million.) At about 17% of total employment, one in every six South Africans who worked, worked in the informal sector – in approximately 1.4 million informal enterprises.

We now consider how informal enterprises differ in respect of having employees or not, or being ‘survivalist’ or ‘growth-oriented’, and so forth. Distinguishing informal enterprises that have employees – and thus are not ‘own-account workers’ (one-person enterprises) – is particularly illuminating. Yet both multi-person and one-person enterprises play a significant role in employment creation.

* Using survey data on informal enterprises – in addition to labour-force data – brings a significant new dimension to the analysis of the informal sector. The millions of people in the informal sector all work in enterprises – whether one-person enterprises or enterprises with employees. This indicates the important institutional context in which these jobs exist: workers are either employees or owner-operators of enterprises.

One-person and multi-person/employing enterprises – and institutional differentiation

Using QLFS data, Rogan and Skinner (Chapter 4 in the book) find that a sizeable component of those working in the informal sector are informal-enterprise operators that also generate employment not only for themselves but also for a million other workers.

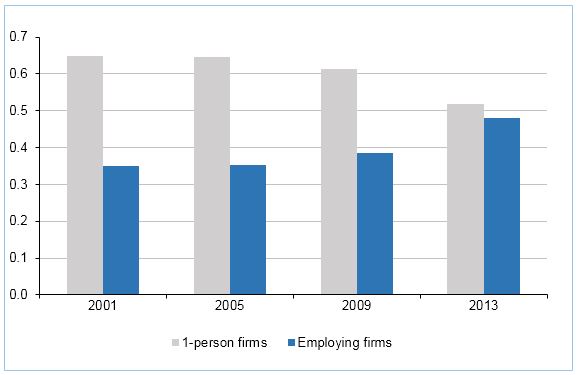

More specifically, the enterprise-based data from the SESE (Survey of Employers and the Self-Employed), used in Chapter 5 in the book, reveal that approximately 80% of the 1.4 million informal enterprises are one-person enterprises and 20% are multi-person, employing enterprises (2013 data). This seems to suggest a sector dominated by own-account workers. However, if one looks at the number of persons working in the enterprises (rather than the number of enterprises), a different picture emerges from the data. Figure 1 shows the share of persons working in multi-person enterprises since 2001.

Figure 1: Share of persons working in one-person and

multi-person informal enterprises

The analysis shows that by 2013 almost half (48%) of those working in the informal sector worked in multi-person firms. This followed a significant upward trend since 2005. In 2013 the 20% employing enterprises provided paid work to about 850 000 people (owner-operators plus paid employees) in addition to approximately 210 000 ‘unpaid workers’ that are probably paid in kind. (As noted in the first article: these 850 000 paid jobs are almost double the direct employment in the formal mining sector – approximately 450 000 in 2013.) The employment contribution of these multi-person, employing firms thus is quite substantial.

An increased employment orientation and employment intensity

The trend shown in figure 1 is part of a larger picture. Since 2001 the percentage of multi-person enterprises has been increasing – from 15% to 21% of informal firms in 2013 – as has their propensity to employ. The average size of these firms has increased (to 3.5 in 2013), and the average number of employees as well as the average number of paid employees has increased.

These changes suggest that there may have been a compositional, or structural, change in the informal sector in the past decade that increased the employment orientation and employment intensity of the informal sector.

The immediate policy implication is that policy should recognise this trend and actively support its continuation. But this raises the question: which factors appear to determine, or influence, the decision to have employees and the propensity to employ? And: can policy affect these factors?

Industry could be one factor. The increased propensity to employ is apparent in almost all industries/sectors except financial services. For example, the informal construction sector stands out for its significantly higher propensity to employ. In contrast, there is no significant relationship between being in trade and enterprises having employees. This suggests that dynamic policy support for the building industry could be important for job creation, in addition to the noted potential positive effects on housing quality and living conditions in townships and informal settlements (see the previous article).

The building industry is traditionally dominated by men. However, well-designed policy measures could train and empower women in preferred building crafts – these crafts should not be men-only occupations in perpetuity. In addition, sectors that are more likely to be populated by women need to be supported as well.

Factors related to how much enterprises are organisationally self-standing, separate from the household

Amongst the factors analysed in relation to the propensity to employ, two stand out: location and financial practices.[2] The results show unequivocally that locational variables have a statistically significant positive association with enterprises having employees. Being operated in the dwelling or not is a key factor in the employment behaviour and profitability of informal firms. Enterprises in home-related locations have significantly lower propensities to employ than those in locations separate from the household. Enterprises in non-residential, commercial locations are also associated with much higher profits. While no simple causality can be concluded in this regard, as discussed below,[3] the importance of access to suitable premises in appropriate locations for informal enterprises is clear.

Unsuitable locations or premises are frequently mentioned in surveys of obstacles identified by informal enterprise owners (e.g. Rakabe, Chapter 11 in the book; also see his Econ3x3 article; Stats SA 2014; Charman 2017). The quantitative results discussed here provide the statistical evidence to substantiate this. It reinforces the need for greater attention of policy-makers to the provision of non-residential premises with essential facilities, services and security in suitable locations with proximity to markets or suppliers.[4] (It needs to be noted, though, that using such a location is often not an option for many women whose household obligations force them to work from home – the hard reality of gender in large parts of the informal sector, notably own-account workers.)

The second key variable is about keeping the finances of the enterprise separate from the household or, simply, keeping accounts of the business. The propensity to employ of owners who keep accounts (or keep business expenditures separate from those of the household) appears to be two to three times as high as the propensity of those who do not (and whose finances are largely integrated with that of the household). Moreover, informal firms that keep accounts have about 70% higher net profits than those that do not.

If there are no separate accounts, or if business revenue flows ‘unobserved’ into the household, the owner-operator cannot properly monitor the business and have a reasonably clear idea of how the business is doing, or pre-emptively identify factors threatening its viability, for example. Simple bookkeeping skills could be readily imparted with targeted training initiatives, for example ‘mobile business clinics’ and/or accounting apps for cell phones that help owner-operators with basic bookkeeping – also emphasising the importance of keeping the business separate from the household (likewise when the owner or another household member is paid a salary from the business’ earnings). Even a home-based enterprise of an own-account worker would benefit from being seen and operated as a financially separate activity.

These two dimensions (separate premises and separate finances/accounts) are important elements in the development and sustainability of informal enterprise activities: spatial and especially financial differentiation signifies the degree of institutional differentiation between the household and the emerging business enterprise. This entails the set of enterprise activities turning into an independent and organisationally stand-alone, self-standing, self-reliant institution. Such an ‘emancipation’ may be important in the continuing development of an enterprise, its profitability and its viability. It could also ease access to banking, credit and other business support services.

A third type of separation is more difficult to attain. It is about shielding the household from the risk of bankruptcy of the enterprise. In the formal sector this can be attained through the legal instrument of limited liability, available only to incorporated enterprises.[5] In contrast, in a formal unincorporated sole-ownership or partnership, for example, a partner is personally liable for losses and debt; usually personal assets must be provided as collateral to obtain business loans from a bank. An informal enterprise owner is in the same position, but is likely to have limited personal assets such as a house or business property, also because titles to land in a township typically are not available, for example. (For risks such as fire and theft the enterprise and the household could be protected by insurance, were it available. Thus it is an important area for policy-makers to consider.[6])

In identifying these dimensions, a specific or prescribed sequence (or causality) is not implied. As different enterprises emerge and develop from ‘embryonic’ states, they will take different routes of maturation, depending on circumstances. Some may start differentiation by keeping separate accounts, become stronger and then feel ready to move to a non-residential location. For other enterprises, for example where the activity demands it, finding a non-residential location may occur first. Whatever the case may be, the point is that the adoption, or manifestation, of these (and other) elements of institutional differentiation could be instrumental in the development of self-reliant enterprises. (Of course, many other factors affect the development and viability of enterprises, for example access to markets. But these are in a different category.)

In general, enabling informal enterprises to develop towards being ‘stand-alone’, self-reliant enterprises can be crucial for attaining viability, employment creation and better livelihoods – whether one-person enterprises or ones with employees. This could be an overarching criterion and consideration for policy. This developmental perspective will be encountered again when formalisation is discussed.

Informal-sector employment growth: significant expansion and entry

The research in the book provides multifaceted new findings on employment expansion as well as entry – the two sources of employment growth (see Fourie, Chapter 5, as well as Lloyd and Leibbrandt, Chapter 6). Given the level of detail in these chapters, a summary of a few core policy-relevant findings must suffice.

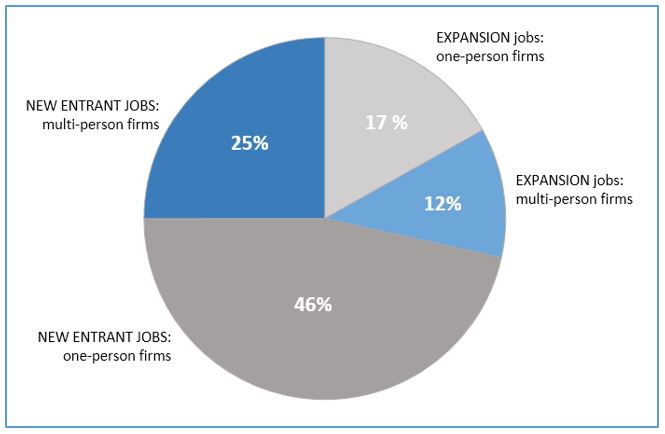

The overall picture of the sources of informal-sector employment growth in a one-year period (2013 data) is as follows:

-

More than half a million (approximately 530 000 jobs) were created.

-

Of these, about 30% came from employment expansion (intensive growth) and 70% from entry (extensive growth); compare figure 2 below.

Employment growth within enterprises

We first consider employment expansion. Though comprising less than 10% of the entire informal sector, more than 90 000 informal enterprises expanded their employment in 2012–2013, producing about 150 000 new jobs in a year (as a rough estimate).[7]

-

Notably, more than 60% of these were prior one-person firms that took in employees, showing that one-person firms do have a role in jobs growth (even if these are a small percentage of all one-person firms). Being numerically the majority, one-person firms provided most of the employment expansion – about 60% of the new jobs.

-

However, enterprises that already have employees (existing multi-person enterprises) have a significantly higher propensity to add employees than one-person enterprises.[8]

-

In the same period, around 60 000 jobs were cut – about 25 000 informal enterprises (about 8% of the enterprises with employees) reduced their employment. This left the sector with net employment expansion of around 90 000 in that year.

Clearly the informal sector is not an inert sector as far as employment expansion is concerned. Moreover, these results put paid to any generalisation that one-person enterprises are without entrepreneurial ambition and do not qualify for policy support with respect to employment creation. Effective enabling measures are likely to elicit much more employment expansion – and these should be available to both one-person and multi-person enterprises.

Employment growth due to new, entering enterprises

Entry by new enterprises is the other, and largest, source of employment growth. Overall, approximately 300 000 new informal firms entered the sector in a 12-month period in 2012–2013 (i.e. they were less than one year old). This amounts to 21% of informal-sector enterprises active at the time of the survey in 2013 (the rest, just above three-quarters, were incumbent owners). Roughly 380 000 new jobs were created in the process.

-

More than 80% of entrants are one-person firms, which produce about two-thirds of new-entrant jobs – in this case, jobs for the enterprise operators.

-

Multi-person entrants create jobs for the owner-operator plus two employees on average (but there are fewer multi-person entrant firms than one-person entrants). This group comprised about 17% of the entrants, but produced about 35% of the start-up jobs. Notably, the proportion of multi-person entrants has been growing over time.

In a related analysis (for two three-month periods in 2013), Lloyd and Leibbrandt find a roughly similar entry rate averaging 26% of informal enterprise owners (Chapter 6 in the book). Clearly, there is no lack of willingness to start new enterprises.

Because these authors used panel data, where the same persons are interviewed in successive periods in time, they could also measure how many enterprise owner-operators exited within the two periods.[9] They find a 26% exit rate within three months (equalling the entry rate). For a combined six-month period, they find that almost 60% of enterprises survive while just more than 40% of enterprise operators exit the informal sector. Undoubtedly, entrant firms are fragile and vulnerable, and many owners soon exit or fail. One-person entrants are especially vulnerable.

The overall picture: sources of jobs in the informal sector

The overall situation regarding the sources of informal-sector job creation is summarised in figure 2. It shows the expansion jobs and new-entrant jobs created by one-person and multi-person firms respectively, as discussed above.

Figure 2: Sources of informal-sector job creation 2012–2013

The significance of entrant owners’ having prior work experience

A noteworthy finding is that the entrant owners that had previous work experience (e.g. formal enterprise ownership or wage employment or informal-sector wage employment) are less likely to exit than owners without prior work experience – and show more promise in terms of turnover and profit. This points to a potentially important role, from a policy perspective, of the prior work experience of entrants and the likely nature of their enterprises (also see Lloyd and Leibbrandt Econ3x3 article).[10]

-

Those who enter from a previously working situation are more likely to keep accounts, keep profits separate from the household, rent premises outside the residence, establish viable, stand-alone enterprises, have some management skills – and employ workers. (They are also more likely to go into manufacturing.) This group comprises about a third of total entrants, but their potential impact on employment, poverty reduction and economic development is significant.[11]

-

Almost all those entering from a non-working situation operate the enterprise from within the household, are likely to work alone as ‘own-account workers’ and have more vulnerable enterprises (mostly in retail). The informal sector absorbs many unemployed persons in the form of own-account workers, but they are the ones most likely to exit soon – most probably into unemployment again. This group comprises almost two-thirds of entrants into informal enterprise ownership. The poverty-increasing impact of such exits of own-account workers could be significant, as shown by Cichello and Rogan (Chapter 9 in the book and their Econ3x3 article).

These are important considerations for enterprise-support policy measures in terms of, for instance, differentiating according to prior work experience.[12] Moreover, own-account workers (one-person enterprises) are more vulnerable; being an employer significantly reduces the probability of exit. This adds weight to the importance of multi-person, employing firms with regard to the provision of stable employment opportunities in the informal sector.

Conclusion

In contrast to labour-force or worker-based analysis, the enterprise-based analysis pioneered in this book enables novel insights into the inner workings of the informal sector and the behaviour of the institutions that provide employment for both owners and employees, i.e. the informal enterprises.

The enterprise-based data and analysis reveal a significant degree of dynamism in the informal sector – many informal firms are entering, many have employees, many are expanding employment, but some are contracting, and failure and exit rates are high. Reasonable measures to enable and support those owner-operators who start or operate informal businesses are critical from a policy perspective:

-

One goal of policy should be to help enterprises to keep going, especially in the vulnerable first months or year (whilst accepting that not all entrants will or can be successful in informal business).[13]

-

From an employment perspective one can argue that policy interventions should attempt to improve the survival rate and durability of informal firms that are growth-oriented – whether still one- or already multi-person enterprises – and try to shield them from factors that could threaten their viability. Non-business factors such as household shocks can also contribute to business precariousness (Hartnack & Liedeman 2016; also see their Econ3x3 article).[14]

-

From a poverty-reduction perspective, helping to keep enterprises of all sizes going is a clear objective.

Lastly, it needs to be noted that such policy support for enterprises, and one-person enterprises in particular, is to be analytically distinguished from forms of social protection that individuals may receive on the basis of considerations such as being unemployed or poor. The second category is something quite different, with a different rationale and different possible policy instruments.

Next extract: Barriers to entry and to ‘stepping up’, including tiers and segmentation; also: business cycle vulnerabilities

Download from HSRC Open Access:

https://www.hsrcpress.ac.za/books/the-south-african-informal-sector-providing-jobs-reducing-poverty

References

The edited extracts are from:

Fourie FCvN (2018) Enabling the forgotten sector: Informal-sector realities, policy approaches and formalisation in South Africa. Chapter 17 in Fourie FCvN (ed) The South African Informal Sector: Creating Jobs, Reducing Poverty. HSRC Press, Cape Town.

Referenced chapters, by number:

4. The size and structure of the South African informal sector 2008–2014: A labour-force analysis – Mike Rogan & Caroline Skinner

5. Informal-sector employment in South Africa: An enterprise analysis using the SESE survey – Frederick Fourie

6. Entry into and exit from informal enterprise ownership in South Africa – Neil Lloyd & Murray Leibbrandt

8. The informal sector, economic growth and the business cycle in South Africa: Integrating the sector into macroeconomic analysis – Philippe Burger & Frederick Fourie

9. Informal-sector employment and poverty reduction in South Africa: The contribution of ‘informal’ sources of income – Paul Cichello & Michael Rogan

11. Prospects for stimulating township economies: A case study of enterprises in two Midrand townships – Eddie Rakabe

16. Informal-sector policy and legislation in South Africa: Repression, omission and ambiguity – Caroline Skinner

Other references:

Bhorat H & Naidoo K (2017) Exploring the relationship between crime-related business insurance and informal firms’ performance: A South African case study. REDI3x3 Working Paper No. 25

Charman A (2017) Micro-enterprise predicament in township economic development: Evidence from Ivory Park and Tembisa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 20(1)

Hartnack A & Liedeman R (2016) Factors that contribute towards informal micro-enterprises going out of business in Delft South, 2010–2015: A qualitative investigation. REDI3x3 Working Paper No. 20

ILO (2015) Recommendation concerning the transition from the informal to the formal economy. Recommendation 204. International Labour Conference. Geneva: ILO

Stats SA (Statistics South Africa) (2014) Survey of Employers and the Self-Employed 2013. Statistical Release PO 276. Pretoria: Stats SA

[1] The idea of formalising the informal economy has received prominence due to the International Labour Organisation’s International Labour Conference 2014 and 2015 deliberations, resulting in Recommendation 204 concerning ‘the transition from the informal to the formal economy’ (ILO 2015).

[2] In addition, older firms are more likely to have employees than younger ones. This points to a need to help informal entrant firms survive beyond the first, vulnerable years so that they can start creating jobs – something scrutinised further below.

[3] As noted in Chapter 5 in the book, already employing and profitable firms may want to move to more convenient, larger business locations away from the home; alternatively, or simultaneously, informal firms already located in non-residential, commercial locations may aspire and be able to expand their activities and staff complement.

[4] The DSBD (Department of Small Business Development), discussed in Chapter 16 of the book, has funds available for developing infrastructure for informal business through the SEIF (Shared Economic Infrastructure Facility) programme. However, there appears to be little uptake on these funds from provincial and local authorities, who must contribute 50% of the cost. In their June 2017 report to Parliament, the DSBD reported R46 million underspending on the NIBUS (National Informal Business Upliftment Strategy).

[5] Indeed, the culminating step in the emancipation process would be to become a limited-liability company and register under the Companies Act, which would imply full formalisation. Typically, a formal-sector corporation displays further forms of role differentiation, i.e. between a board of directors, managers, employees and the owners of shares (capital suppliers). Each of these capacities plays a different role in the firm and is mostly occupied by different people (see Fourie 1996).

[6] Bhorat and Naidoo (2017) find a significantly positive relationship between being covered by business insurance and enterprise performance. Yet insurance is seldom mentioned by commentators as a potential support measure.

[7] In Chapter 5 in the book the author warns that these results unavoidably had to be based on relatively small samples. Accordingly, the standard errors on the employment-growth results are relatively large, implying lower accuracy than one would ideally want. On the other hand, there is no other way to get a first look at employment-growth behaviour in the informal sector. But one must be satisfied to see these numbers as approximate values.

[8] Multi-person firms’ propensity to expand employment increased in the post-2009 upswing phase, a typical business response to improving business conditions. Compare Burger and Fourie, Chapter 8 in the book.

[9] Unfortunately, the nature of such panel data is such that one can only analyse changes over short periods of time, e.g. three months or six months.

[10] Charman (2017: 10–11), from a case study in two Midrand townships, distinguishes four typical pathways into informal business: (1) Starting out as a pure livelihood strategy with what is referred to as ‘make-work jobs’ to make ends meet. The business then unfolds, developing to a scale unimaginable at the outset and becomes permanent. (2) Acquiring skills, on-the-job experiences and access to customers through working someplace, then going on to establish an own, related business. (3) Investment by wealth holders in a business that they do not necessarily run, either setting up a new shop or buying out struggling businesses such as spaza shops. (4) Acquiring a business when it is passed on within an extended family, especially if it has a licence, permanent structure or accumulated business assets. The first of these four pathways is a transition from ‘not-working’ to ‘ownership’, the second a transition from ‘working’ to ‘ownership’.

[11] The analysis of Lloyd and Leibbrandt also reveals a substantive flow (about 23%) from informal-sector wage employment to formal-sector wage employment (and vice versa). The flow from informal-sector wage employment to informal enterprise ownership is substantially less (less than 3%). This is not surprising, given the difference between the decision to search for employment and to start a business (without even considering the barriers to entry facing a business start-up). Both personal characteristics (such as risk aversion, entrepreneurial inclination or level of education) and business- or market-related factors (such as market opportunities, or entry barriers such as suitable premises and sufficient start-up capital) are likely to play a role.

[12] This suggests that encouraging the formal sector (public or private) to offer internships may have a positive effect on prospects not only in the formal sector but also the informal sector. Public works programmes may also be useful in this regard.

[13] Business always is a risky venture and if the owner does not do sufficient planning and/or does not have the wherewithal (personal acumen, skills, capital or premises) for a viable enterprise, policy support may not be apposite, or must at least not go beyond some point. Some entrants may just be trying to get by for a period without having any real intention to establish a sustainable business. From a policy effectiveness and affordability viewpoint, well-founded targeting and selection will have to be part of policy design.

[14] In a study of the Delft township, Hartnack and Liedeman (2016) provide evidence that among informal micro enterprises which were operational for several years, a combination of broader socioeconomic constraints (e.g. new forms of competition, increasing state regulation, crime and neighbourhood conflict) and unexpected household shocks (e.g. family sickness, death, imprisonment, retrenchment) play a crucial role in enterprise closure, in addition to deficiencies in business models or inadequate management skills.

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.