The informal economy: Is policy based on correct assumptions?

What do policy makers ‘want’ from the informal sector and the informal economy?

In a way, the answer to this question is simple: to provide jobs. While much of the attention that is currently being paid to job-creation policies focuses on the ‘township economy’ (or ‘the township and village economy’ – see ANC 2019), the National Development Plan (NDP) outlines ambitious employment targets for the informal sector. The NDP projects that the informal sector (plus domestic work) will create between 1.2 and 2 million new jobs by 2030.

In particular, the NDP also expects the informal sector to absorb jobs that are lost in the formal sector. Following the claim of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) that the informal sector acts as a ‘shock absorber in times of economic crisis’, the NDP expects the informal sector to ‘provide a cushion for those who lose formal jobs or need to supplement their formal incomes during crises’.

In 2014, the Department of Trade and Industry released the National Informal Business Upliftment Strategy (NIBUS) as the first nationally coordinated policy and approach to dealing with informal businesses. This document, and the accompanying Roadmap to implementation of 2016, that was spearheaded by the Department of Small Business Development (DSBD), are both underpinned by the idea that informal businesses will graduate into the mainstream (DTI 2014: 28). A range of support measures, including access to finance, training and infrastructure, are outlined. The NIBUS document focuses on ‘informal businesses’ which are defined as ‘entrepreneurial activities within the informal sector’.

At the provincial level, the job-creation policy focuses on the township economy. Several provinces have developed or are developing strategies to develop the township economy, with Gauteng leading the way. According to Premier Makhura, the aim of their strategy is the ‘significant participation and meaningful inclusion of the people of the township into mainstream economy … The townships must be self-sufficient and [have] vibrant economic centres’ (Gauteng Province 2015). This vision has been echoed frequently since. There has been considerable technical back-up from the South African office of the World Bank (see, for example, World Bank 2014). While none of these documents gives a precise definition of the township economy, the language used in them refers to entrepreneurship and small business, so it would include (but not exclusively) what Statistics SA defines as the informal sector.

At a local government level, as Skinner (2018) outlines, policy statements frequently cite the informal sector’s positive contribution to job creation, but city-level actions are ambivalent and sometimes actively hostile. The Johannesburg City Council’s 2013 Operation Clean Sweep in which 6 000 street traders were removed is a case in point. Research suggests that there is a systematic exclusion of informal operators from inner cities. Even in cities like Durban, which has been hailed as having a relatively progressive stance, the City Council’s actions reflect a more ambivalent approach. Several cases have occurred of informal operators’ being threatened by the development of shopping malls, being harassed or having their goods confiscated (Skinner 2017).

There is a parallel stream of policy work on ‘formalising the informal economy’, which has been given impetus by the International Labour Organisation’s 2015 recommendation 204 on transitioning from the informal to the formal economy (ILO 2015). The Department of Labour is overseeing a process of implementation of what is referred to as R204 through the National Economic Development and Labour Council (NEDLAC). The process concentrates on informal employment or unprotected work (both inside and outside the informal sector). This is a welcome broadening of the policy focus to add improved work conditions and social protection and is informed by the notion of decent work.

Despite the apparent contradictions in the various policy approaches to the informal sector and the informal economy, it is safe to assume that this segment of the labour market is seen by at least some policy makers as an important way to promote employment and economic growth.

Who or what is the target of policy?

There is clearly is a lack of conceptual clarity about who or what is being targeted by different policies – with gaps emerging. For example, the DSBD’s focus on informal business and entrepreneurial activities within the informal sector runs the risk of missing the smaller players, who might not be considered ‘entrepreneurial’. Also, while the focus on townships is welcome, as will be noted below, the informal sector is prevalent in informal settlements and in rural and communal areas – and arguably it is in particular need of support there. In addition, the township economy includes formal businesses and the strategies tend to emphasize business and entrepreneurs, while giving little attention to own-account informal operators such as educare providers, waste pickers and street traders. Women tend to dominate in these, less lucrative, activities.

The International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) outlines internationally agreed definitions that Statistics SA applies. Policy makers would do well to use these when they develop their strategies. According to the ICLS, the ‘informal sector’ refers to employment and production that take place in unincorporated, small or unregistered enterprises while ‘informal employment’ refers to employment without social protection through work both inside and outside the informal sector. The ‘informal economy’ refers to all units, activities and workers so defined and their output.

The ICLS is following the mandate of the International Labour Organization that has spearheaded an international broadening of emphasis from enterprises to employment and promises to advance a holistic approach. The focus just on informal-sector enterprises has long sidestepped the issue of poor working conditions and social protection deficits. We favour an approach to informal employment that considers the multiple needs of informal operators as workers and entrepreneurs working in different locations and in different segments of the economy.

We turn to the question of whether labour-market data support the focus and assumptions of the current policy. While we advocate that policy should focus on the informal economy, our analysis below concentrates on one component of the informal economy, the informal sector, since it draws from work done for the Informal Sector Employment Project within the REDI3x3 project (see Rogan & Skinner 2017; 2018).

Is the informal sector a shock absorber?

An analysis of the informal sector during the 2008 financial crisis and the ensuing recovery period offers some important insights. Figure 1 shows that the informal sector consistently accounted for 16-18% of all non-agricultural employment between 2008 and 2014.

Figure 1. Non-agricultural informal-sector employment as a percentage

of total non-agricultural employment (2008-2014)

The key finding is that, over the six-year period that included the single largest cyclical shock to the post-apartheid economy, the informal sector, at the aggregate, was not absorbing the jobs that had been ‘lost’ in the formal-sector. Indeed, particularly during the crisis period (2008-2009) in which aggregate job losses were experienced, informal-sector employment declined relatively more than formal-sector employment. At the height of the crisis (the third quarter of 2009), the informal-sector share of total non-agricultural employment decreased to as low as 16%.

While the main longer-term finding is that the size of the informal sector, as a percentage of the non-agricultural workforce, has remained relatively constant, the implication is that the informal sector did not act as a ‘shock absorber’ during a significant economic crisis. Thus, the assumption of a key policy document (the NDP) that the informal sector will regularly absorb jobs lost in the formal sector does not appear to be supported by the evidence.

What are the spatial dimensions of informal-sector employment?

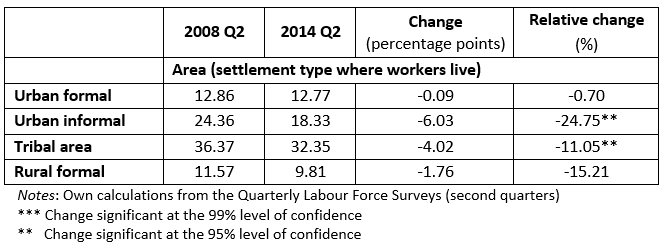

Table 1 shows that employment in the informal sector makes up a much larger share of total employment for households in the deep rural parts, followed by households in urban informal settlements. In 2008, for example, about 36% of non-agricultural employment in the tribal areas was in the informal sector (column 1). This is not necessarily a new finding and is closely linked with the legacy of spatial planning during the apartheid era. It does, however, reinforce the importance of the informal sector for job creation in places where poor households are concentrated.

With specific reference to the township economy, in 2014 about 13% of the workforce living in formal settlements in urban areas and 18% of the workforce in informal settlements in urban areas worked in the informal sector. Therefore, the informal sector is an important livelihood source particularly for households in informal urban settlements.

Table 1. Informal-sector employment by area type as a percentage

of total non-agricultural employment

When one looks at the period between 2008 and 2014 as a whole, there was a significant overall decline in the informal sector as a source of employment for those living in these informal settlements in urban areas. As a share of total non-agricultural employment, this share decreased by about 25% in relative terms (from about 24% to 18% of total employment).

If this declining share of informal-sector employment was accompanied by an absolute increase in employment in the formal sector or a decrease in the unemployment rate (i.e. among households in urban informal areas), then there would be no cause for concern. The data suggest, however, that this has not been the case over this particular period. The actual number of formal sector jobs (not shown in the table) did increase but so did the broad unemployment rate in urban informal areas (from 29.4% in 2008 to 35.8% in 2014).

Against this backdrop of an increasing unemployment rate, the decreasing share of informal sector employment among workers from urban informal areas raises some questions about the ‘township economy’ and its current contribution to the growth of employment in townships and settlements. In other words, the data suggest that employment in the informal sector is a smaller and decreasing share of employment for households based in poor urban areas (relative to the deep rural parts of the country). The informal sector is, therefore, much more than what policy documents see as the township economy.

What should the policy emphasis be?

These findings show that, contrary to expectations, there were significant and disproportionate job losses in the informal sector during the 2008–9 global crisis. The policy implication is that the informal sector, rather than being a buffer (or ‘cushion’) in times of crisis, might in fact need extra policy support during recessionary periods. Studies in several different contexts have shown that the informal sector is not, as a rule, a residual employment category which absorbs displaced workers from the formal sector (Mehrotra 2009). Rather it is an integral component of the country’s economy.

What then should be done to ensure that the informal sector contributes to employment growth and decent work? This is not an easy question to answer and there is certainly no consensus, but there are several possible suggestions.

The critical first step is ‘do no harm’ measures. By way of example, regulations like municipal by-laws often criminalise work in the informal sector and need to be redrafted. Recent work by the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa has shown the way with respect to street traders (see Clark 2018 and Fish Hodgson & Clark 2018). If we are serious about supporting the informal sector or ‘township’ economy, we should not assume that it will expand and grow on its own amidst contradictory, opaque and even hostile local regulations and municipal practices. Just like firms in the formal sector, informal operators require certainty and consistency in the policy environment.

In addition to the frequent emphasis on access to financial services and training, research on the informal sector demonstrates that investing in the relevant infrastructure has an important and positive impact on the resilience and productivity of informal workers (see Fourie 2018). Those working in public spaces need access to basic infrastructure such as water and toilet facilities, as well as infrastructure to support their work, e.g. shelter, storage and sorting facilities (e.g. Dobson & Skinner 2009). Further, their homes are the workplace of many informal workers, for example spaza shop owners, or those doing small-scale catering and manufacturing, to name a few. Too little attention is paid to this in approaches to the upgrading of informal settlements and low-cost housing developments.

And finally, the many ways in which informal and formal economies are interlinked need far greater attention. Philip, for example, has shown how the structure of the formal economy shapes, and sometimes crushes, opportunities in the informal sector (Philip 2018). Detailed analyses of value chains – like that of Tsoeu (2009) on the shebeens and South African Breweries (which shows that 82% of SAB’s final sales in the country is in the informal sector) – could inform more sophisticated policy interventions. These would also show how macroeconomic, trade, industrial and competition policy, among others, all have implications for those working in the informal sector.

If we are serious about implementing policies which support informal work then a logical starting point would be to get the very basics right in terms of regulations and infrastructure. These and more sophisticated interventions need to be informed by information on where informal workers can fit into broader value chains. That said, it is important not to romanticise working in the informal sector. Our research has shown that working hours are long, working conditions are often difficult and earnings and returns are very low for all but a few (Rogan & Skinner 2017; 2018). In this regard the NEDLAC working group on the implementation of R204 is critical to tackling decent work and social protection deficits.

References

African National Congress, 2019. Election Manifesto.

Clark M (2018) Towards Recommendations on the Regulation of Informal Trade at Local Government Level. Socio-Economics Rights Institute and the South African Local Government Association.

Department of Small Business Development and the International Labour Office (2016) Provincial and Local Level Roadmap to give effect to the National Informal Business Upliftment Strategy, Policy Memo. Pretoria.

Department of Trade and Industry (2014) The National Informal Business Upliftment Strategy (NIBUS). Policy Memo. Pretoria.

Dobson R & Skinner C (2009) Working in Warwick: Including Street Traders in Urban Plans. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Fish Hodgson T & Clark M (2018) Informal Trade in South Africa: Legislation, Case Law and Recommendations for Local Government. Socio-Economics Rights Institute and the South African Local Government Association.

Fourie FCvN (2018) Informal-sector Employment in South Africa: An Enterprise Analysis. In Fourie FCvN (ed), The South African Informal Sector: Creating jobs, Reducing Poverty, HSRC Press.

Gauteng Province Economic Development Department (2015) Gauteng informal business upliftment strategy. Johannesburg: Policy memo.

International Labour Organization (2015) R204 - Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy Recommendation, Geneva.

National Planning Commission (2012) National Development Plan: Vision for 2030, Our Future – Make it Work. Pretoria: NPC.

Mehrotra S (2009) The Impact of the Economic Crisis on the Informal Sector and Poverty in East Asia, Global Social Policy, Vol 9

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, n.d. Informal Employment and the Economic Crisis.

Philip K (2018) Limiting Opportunities in the Informal Sector: The Impact of the Structure of the South African economy in Fourie FCvN (ed), The South African Informal Sector: Creating jobs, Reducing Poverty, HSRC Press.

Rogan M & Skinner C (2017) The Nature of the South African Informal Sector as Reflected in the Quarterly Labour Force Survey, 2008-2014, REDI3x3 Working paper 28, February 2017.

Rogan M & Skinner C (2018) The Size and Structure of the South African Informal Sector: A Labour Force Analysis in Fourie FCvN (ed), The South African Informal Sector: Creating jobs, Reducing Poverty, HSRC Press.

Skinner C (2017) The Role of Law and Litigation in Street Trader Livelihoods – The Case of Durban, South Africa, Rebel Streets, Informal Economies and the Law, (ed) Alison Brown, London: Routledge.

Skinner C (2018) Informal Sector Policy and Legislation in South Africa: Repression, Omission and Ambiguity in Fourie FCvN (ed), The South African Informal Sector: Creating jobs, Reducing Poverty, HSRC Press.

Tsoeu M (2009) A Value Chain Analysis of the Formal and the Informal Economy: A Case Study of South African Breweries and Shebeens in Soweto, Masters Dissertation in Industrial Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand: Johannesburg..

World Bank (2014) Economics of South African Townships: A Focus on Diepsloot. Washington DC: World Bank Group.

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.