The politics of economic change

Introduction[1]

Despite multiple policy interventions, South Africa has not made significant progress in achieving growth-enhancing structural transformation. In fact, since 1994, the economy has prematurely deindustrialized, with manufacturing’s contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) declining from 21% in 1994 to 12% in 2019 in favour of services. Moreover, the shift has been mainly to lower-value, lower-productivity services, and the growth of financial services has not been accompanied by significant growth in employment in the sector, nor by higher levels of savings and investment in the real economy.[2]

Within manufacturing, growth has continued to be biased towards mineral- and resource-based industries that were at the industrial core of the economy before 1994. The slow progress of transformation of the industrial structure is reflected in South Africa’s undiversified exports. Mineral and resource-based industries continue to dominate the export basket, accounting for approximately 60% of merchandise exports in 2019.[3]South Africa is thus missing out on the gains from international integration in improved competitiveness.[4]

The failure to achieve structural transformation has also had implications for socioeconomic outcomes, including unemployment, inequality, and increased participation in the economy.

Why has South Africa had such a poor record, particularly as the economic policy objectives of successive post-apartheid administrations have been to support more diversified and labour-absorbing industries? To answer this it is necessary to understand the power of different interests and how they have influenced policy choices, design, and implementation.[5]

Political settlements and industrial development

The success or failure of structural transformation depends on changes in the distribution and configuration of power among different interest groups, that is, in the ‘political settlement’.[6] The nature of industrial development depends on whether the political setllement supports the design and implementation of policies with incentives for, and conditions on, firms to ensure high levels of investment and technological upgrading.

Successful industrial development relies on the ability of the state to create and manage rents necessary for driving structural change. The political settlements framework is a useful lens through which to examine how states’ capabilities to manage these rents to ensure productive investment for growth are influenced by the distribution of power within a society.[7]

The political settlements framework critiques the “good governance” agenda, which promotes the adoption of institutions that enforce the rule of law, a democratic political election system, low levels of corruption, transparency of the state, and limited restrictions on the private sector.[8] The ‘good governance’ agenda has its roots in New Institutional Economics (NIE), which has struggled to explain huge differences in the development trajectories of countries that adopted this agenda.[9]

For instance, the NIE emphasizes competition with liberalized markets and independent institutions as the primary requirement for economic development. However, this supposes that competition simply arises in the absence of obstacles, and fails to recognize the need to address entrenched inequality and economic power.[10]

Neither does the new institutionalism engage with the ‘path-dependent’ nature of development—meaning that firms that have already developed productive strengths are able to re-invest and grow their businesses.

By comparison, the political settlements framework asks how powerful elites organize through formal and informal institutions, especially during transitions, to sustain economic benefits? How do the organizations formed maintain social and political stability to distribute economic benefits in line with distributions of power, and how might new coalitions form?

Industry experiences: South African case studies

The political settlements underlying South Africa’s structural change dynamics are reflected in conflicts over value capture in the industrial groupings that form the core of the economy. These include metals and machinery, chemicals and plastic products, food and beverages,[11] fruit, and automotive industries.

The better performance of upstream resource-based industries compared with the more diversified downstream sub-sectors, into which these resource-based basic products are inputs, is evident in the studies of metals and machinery, and chemicals and plastic products.[12] Neither industry grouping has managed to diversify or build stronger capabilities. Indeed, the downstream and more diversified parts of the value chains have performed poorly compared with the upstream parts of the chains.

Within each industry, however, there are pointers to the potential for growth. For example, there are segments within the machinery and equipment sub-sector that can meet the specialist requirements of different types of mining operations, in which South Africa has developed world-leading capabilities. But the country has failed to build on these niches of advanced capabilities. In the plastic products industry, from 1994 to 2002, when tariffs were liberalized, local firms competed effectively with imports and grew output and employment. Crucially, during this period the monopoly input supplier, Sasol, was constrained in its pricing to local customers, as it had committed to export prices for key products (as a condition of state support). But as the regulatory regime altered, Sasol’s[13] strategy towards the local value chain changed, and it began maximizing prices by charging local firms import parity prices.[14]

Government has also continued to support the upstream basic metals and chemicals sub-sectors. This is puzzling from the political economy perspective: why have capital-intensive resource-based industries received substantial support, while downstream, labour-absorbing industries generally have not. Part of the answer lies in the challenges of competitiveness in these sub-sectors within the global context, and part lies in the ongoing influence of the large upstream firms.

Different factors have driven the performance of the automotive and the food industries. These are both large industries in South Africa, accounting for 7.2% and 14.8% of manufacturing value added respectively in 2019.[15] The automotive sector has been assisted by a targeted industrial policy. Outside of resource-based sectors, it has recorded by far the best growth in manufacturing, yet the capabilities remain shallow and focused at the assembly level.[16] The automotive industry has continued to run a significant trade deficit, while the record in growing local content has been relatively poor. The automotive industry reflects a skewed arrangement that favours the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs).[17] This is partly due to the successful lobbying of the large OEMs for support, and is perhaps unsurprising as the threat of the loss of jobs in unionized factories has held greater weight than the potential employment that could be generated by better policy support.

The food and beverage industries consist of a range of value chains extending from agriculture and agro-processing to retail. There have been some successes, notably the rapid growth of fresh fruit production based on export markets and wine exports. Under apartheid, there was extensive regulation and support for agriculture and the food-value chains. The widespread liberalization of markets in the 1990s brought far-reaching restructuring with large employment losses in many segments. Many food processing cooperatives became privately owned with some acquired by multinational conglomerate groupings.

The fresh-fruit industry has emerged as a strong export generator. A key factor in its success is coordination along the value chain to deliver higher-value products to meet the preferences of export markets, made possible in part by the privatisation of former cooperatives. But these successes have resulted more from effective producer strategies than targeted government strategy, though there have been some attempts to rectify this.[18] The citrus industry in particular exemplifies a development coalition, whereby different interests have worked together and this has culminated in South Africa being the second largest exporter of citrus in the world.

An open economy but signs of structural regression

In the 1990s and 2000s, South Africa became an extremely open and internationalized economy in terms of trade, capital flows, and ownership. While these changes brought far-reaching restructuring in industry, they did not result in diversification or sustained higher levels of investment.[19]

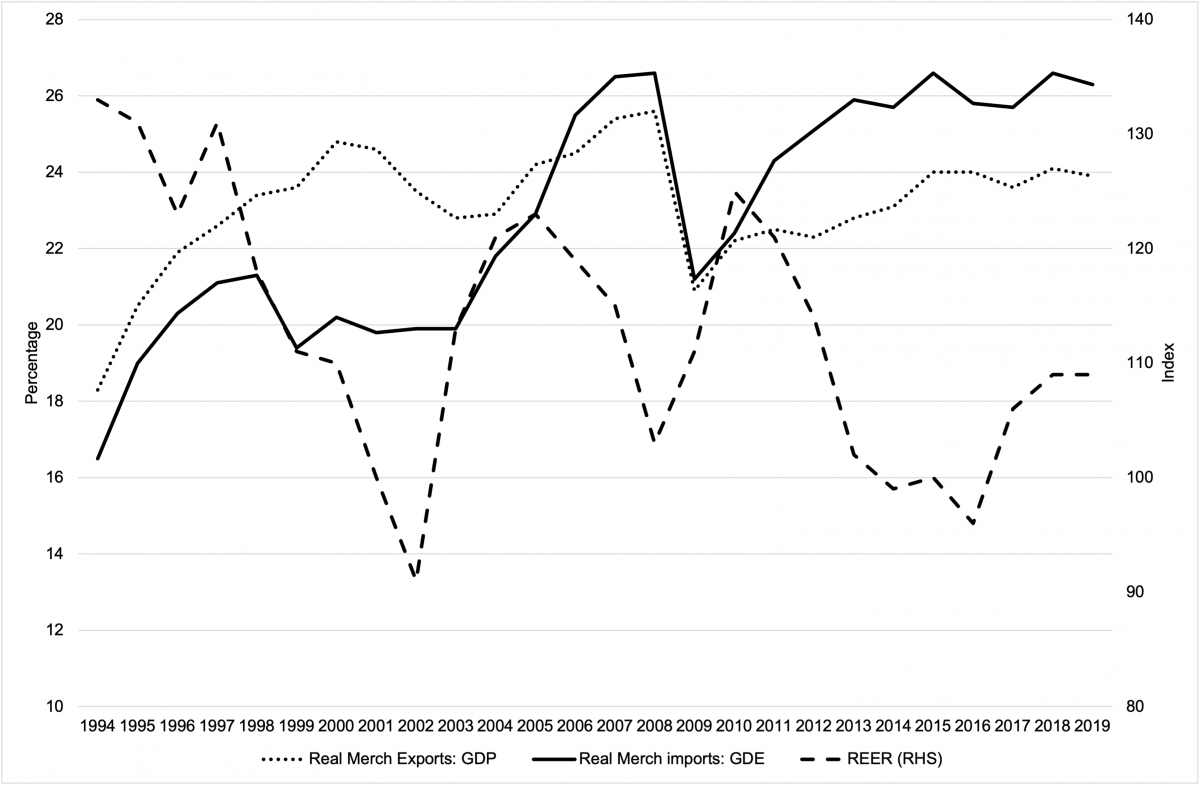

In terms of international trade, the liberalization in the 1990s heralded much higher levels of exports and imports. From 1994 to 2002 the real exchange rate weakened, as was appropriate under reduced protection. While import penetration increased so did the ratio of merchandise exports to GDP, from 18% in 1994 to 25% in 2000, opening up a trade surplus. This included increased exports in diversified manufacturing industries including machinery and equipment and motor vehicles. But imports also grew substantially in these and other manufacturing sub-sectors.

From 2002, however, the strengthening exchange rate underpinned by the focus on inflation targeting meant imports increased strongly to reach 27% of gross domestic expenditure (GDE) in 2008. (See Figure 1) . The new imports were largely of diversified manufactured products and undermined local producers who could not compete with them. The increase in imports in fact exceeded the higher earnings from minerals exports and the country went into a trade deficit during the international resources boom to 2008. The end of the boom saw much poorer export earnings, while the hollowing-out of diversified productive capabilities meant a widening trade deficit once again from 2011.

Fig. 1 Trade and the real effective exchange rate

Source: South African Reserve Bank data.

Instead of the hoped-for export-led growth, far-reaching liberalization and international integration led to a hollowing out of industries. Growth in manufacturing value-added has continued to be biased towards mineral and resource-based sub-sectors. There has been a decrease in manufacturing employment across the board, but the largest losses have been borne by exactly those diversified manufacturing industries where strong growth would create jobs.

South Africa’s openness to the global economy has also meant that it has been exposed to global commodity price volatility. This is evident in the huge swings in steel prices. The downturns have resulted in local producers lobbying for support, while in years of high prices the profits have been taken out of the business.

South Africa’s liberalization of capital flows has seen large volumes of portfolio and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows and outflows. As South African companies such as SABMiller and Naspers have become part of huge transnational corporations (TNCs), the capitalization of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) has increased to more than 300% of the country’s GDP. But this has not meant higher levels of fixed investment in South Africa. Capital account liberalization has also allowed South African corporations to move capital abroad on a grand scale, both legally and illegally.[20]

The rise in portfolio and FDI inflows has been matched by an increase in foreign ownership of the JSE, from 4% in the late 1990s to 25% in 2018.[21] The significance of TNCs in South Africa’s economy exceeds global trends, which show individual corporations controlling resources (at least in monetary terms) and having security, intelligence, and public relations operations larger than many states, as well as significant lobbying capabilities, such as through donations to political campaigns.[22]

International ownership of key businesses in South Africa has, in some industries, been part of a deliberate government strategy. In the case of basic steel, the strategy was to find Iscor an international equity partner to enable access to technology and investment.[23] Ultimately, the company became absorbed into ArcelorMittal, the largest steel transnational corporation in the world. The local business became peripheral to the parent, given the relatively small domestic demand and low levels of growth, and the parent company did not invest in R&D in the South African business. The weakening of historical cost advantages meant it was vulnerable to commodity price swings, while subject to transfer pricing and profit shifting by the parent company.

Key insights from the industry experiences

Political settlements are stable when the distribution of rents is in line with the distribution of economic power. This suggests that powerful groups can be identified by studying the patterns of rents or benefits of economic policy. The key insight from the discussion of industry experiences is the consistently strong performance by upstream industries and poor progress in diversifying the economy. There have also been sustained high-profit levels in some sub-sectors of services.[24] These outcomes point to the weight of path dependency that needs to be addressed for a change in direction. Industrial and economic policy should play a key role in this. However, success in effecting this change depends on the extent to which powerful interests or groups support this diversification. Three important observations from the industry experience can be made.

First, the patterns of performance were reinforced by the adoption of liberalization policies, without accompanying industrial strategies to support new businesses and thus it mainly benefited the established large and competitive firms in the economy.

Second, the industry experiences indicates government’s continued support of the large incumbents, despite industrial policies that support diversification.

Third, the lack of industrial diversification also reflects problems with coordination across policy areas that include energy, minerals, and infrastructure. Understanding the underlying factors in poor policy coordination is important, particularly if this failing is a result of conflicts of interests—as appears to have been the case.

The main groups engaged in conflicts over policies, rents, and coordination have essentially been established businesses, previously excluded black capitalists and entrepreneurs, industry associations, trade unions, and the government and its constituencies. The previously excluded black capitalists have been fragmented in small black elites often with ties to the ruling political party, and independent black entrepreneurs. Industry associations have provided important platforms for engaging on policy and have generally been made up of combinations of entrenched firms, black capitalists, black entrepreneurs, and entrepreneurs more generally. The trade unions representing workers have focused on the interests of the existing workforce, meaning that these have been largely aligned with the existing economic structure. The unemployed and new market entrants have not been sufficiently organized to counteract the influence of entrenched firms on economic policy. For its part, government has been the arena where conflicts of interests play out rather than a strong voice for the former groups.

The political settlement and its effects on industrial development

South Africa’s democratic economic policy can be assessed in three phases that roughly coincide with the presidential tenures of Presidents Nelson Mandela (May 1994 to June 1999), Thabo Mbeki (June 1999 to September 2008), and Jacob Zuma (May 2009 to February 2018). The period under President Cyril Ramaphosa (from February 2018) is too short to properly assess, while President Kgalema Motlanthe (September 2008 to May 2009) was an interim president for less than a year.

The 1994 compromises: A settlement to end apartheid

The compromises reached in 1994 left the economic structure intact, in effect continuing to protect white ownership of wealth and privileged employment positions of the existing workforce for at least five years in exchange for improvements in labour rights. The compromises were premised on the expected growth on the part of established businesses. The major changes were the liberalization of trade and capital flows, the deregulation of agricultural markets, and moves towards privatization. These choices effectively de-prioritized redistribution and inclusion.

The compromises reflected the relative power of big business interests. Business had invested heavily in influencing the economic policy-thinking for the democratic era. This included engaging with the stakeholders leading up to and during the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) negotiations in 1991, providing technical support and data for scenario-planning exercises, and punting a market-friendly environment that informed both the ANC and the National Party in the coalition government.[25]

Recognizing the potential power of black entrepreneurs, big business initiated the principles and practice of black economic empowerment (BEE), with its emphasis on ownership transfers to influential individuals (linked to the ANC), to secure buy-in for orthodox reforms. These BEE deals started long before the actual legislation came into effect and served to significantly shape it.

Big business sought to mould institutions and set the rules of the game, to protect its interests.

The diagnosis of competitiveness focused on the low productivity levels attributed to protection from import competition. As a result, the policy recommendations emphasised fostering the role of market incentives and strengthening underlying capabilities in human resources and technology in order to facilitate industrial restructuring.

This was aligned with the orthodox economic ideology at the time, which emphasized fixing the fundamentals and allowing market forces to do the rest, rather than adopting targeted industrial policy to shape the development path. This can be illustrated by the developments in competition law and policy.

The high levels of concentration and lack of competition in many sub-sectors were acknowledged as a challenge for a growing economy. However, the Competition Act of 1998 negotiated by government, labour, and business, emphasized market efficiency and did not directly tackle the extreme concentration of control by dominant firms in many markets. It was a reflection of the balance of power between the key constituencies and the strength of big business in particular.[26] The choices made mattered for structural transformation, as the strategic conduct of incumbents can raise entry barriers, exclude smaller businesses, and undermine capability development and diversification.[27]

The ‘holding power’ of big business at the time of the legislation was a reflection of government’s concern about investment levels in the economy, and the implicit threat of not investing if the environment was not conducive to ‘business certainty’. This was reflected in the significant changes made between the government’s initial draft and the final provisions.[28] As a result, even though the Competition Act acknowledges the objective of wealth redistribution, the provisions meant to deal with abuse of a dominant position have been limited.

At the same time, macroeconomic policy emphasized ‘stability’. This was despite alternatives that were on the table, including the ‘framework for macroeconomic policy in South Africa’ proposed by the ANC’s Macroeconomic Research Group (MERG). The MERG framework emphasized an initial public investment-led approach for the 1990s and sustained growth in the 2000s underpinned by supply-side industrial policy interventions to alter the development trajectory.[29] The rejection of the MERG proposals by President Mandela and Deputy President Mbeki followed the critique by the white business community which labelled them as ‘macroeconomic populism’.[30] Reassurances to local and international business meant the developmental state ideas were abandoned.

The more things change: 2000–2008

Under Mbeki, the political settlement remained largely intact, albeit with some important additions. While liberalization, open markets, and macroeconomic stability continued as policy, this was supplemented by expanded ‘market friendly’ incentives to encourage ‘knowledge-intensive’ activities and advanced manufacturing technologies.[31] Higher levels of investment were expected from business in response. However, there was no understanding of the relationship between the economic structure and investment in capabilities and, instead, deindustrialization continued as downstream and diversified manufacturing performed poorly. In practice, moreover, the incentive programmes tended to support the capital-intensive upstream industries.[32] By the mid-2000s there was still no overall policy that aligned different interventions.[33]

Though there was a range of incentives to promote investment, exports, and technological improvements, and to support small firms, these were largely soft-touch measures targeted at the same industries that received support from the apartheid government, and did little to change the structure of the economy. The three manufacturing and tradeable sub-sectors specifically supported by government between 1994 and 2007 were automotive, resource-based industries (steel, chemicals, and aluminium), and clothing and textiles. These incentives included the accelerated depreciation allowance and the Strategic Industrial Projects (SIP) programme. Both were made available to large capital-intensive projects, mostly in resource-related sub-sectors such as steel, ferro-alloys, aluminium, and basic chemicals.[34] The rationale for continuing to support upstream industries was based on opportunities for development through linkages to the downstream industries. However, there were no conditions placed on these incentives and there have been limited benefits for linked industries.[35]

With the commodities boom driven by Chinese demand coupled with domestic consumer credit extension and investment for the World Cup in 2010, the economy grew even while cheap imports on the back of the strong currency were hollowing out local manufacturing. At the same time, the need to bridge the gap between South Africa’s ‘two economies’ meant social grants were increased along with greater spending by government and parastatals on extending basic services.

The approach to BEE reflected this attempt to straddle divergent realities as business committed to voluntary charters with weak monitoring and an absence of enforcement.[36] BEE effectively reinforced the existing economic structure and left black shareholders in debt to their white business partners. Large businesses successfully lobbied the government not to implement structural changes that would create opportunities for entrants, including black entrepreneurs, in exchange for firms creating BEE initiatives that effectively reinforced their position as gate-keepers in the economy. This was despite a detailed program of the BEE Commission that aimed to bring empowerment and structural transformation, together with an emphasis on increased productive investment.[37]

Many of those driving BEE policies became beneficiaries of the ownership transfers and have become multi-millionaires. This weakened the holding power of the remaining black entrepreneurs as there was now a policy to address their concerns, even if the instruments were weak. By 2015, the distribution of the value of BEE deals was largely in line with the economic structure in 1994. Mining attracted the highest share (32%), followed by industrials representing 18% of the total value.[38] The strategies of the emerging black elite were to establish BEE holding companies that took minority shares in multiple existing companies to spread risk rather than deepening ownership and control and making new net investments. Few BEE beneficiaries have moved into diversified manufacturing activities; those that have diversified their portfolios have tended to move into financial services.

The poor design of BEE also undermined the use of public procurement to drive diversification and productive inclusion. The application in practice meant that empowered importers could be prioritized over domestic producers. This came at the cost of domestic production and jobs.

On the labour front, most semi-skilled and unskilled workers, and many of the informally employed and unemployed, were progressively excluded. While popular protests grew, these were suppressed by policing, and social grants were substantially expanded to mitigate the short-term effects of deindustrialization.[39]

Individual ministries developed strategies to support advanced manufacturing and create employment, but there was little coordination between them.

Towards the end of this period it became apparent that structural change towards more diversified industries was necessary to drive growth and to address the high levels of unemployment and inequality. As part of the Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative of South Africa (ASGI-SA), the National Industrial Policy Framework (NIPF) was introduced in 2007. The NIPF identified the need to coordinate interventions and target sub-sectors for industrial development. The focus of the strategy was on diversifying the economy towards downstream labour-absorbing industries. However, the industrial policy did not reflect the prevailing distribution of power within the economy. As such, it has not been successful and is considered a project of the Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition (DTIC) rather than part of a government-wide coordinated strategy.

Populism and state capture, 2008–18

Growing popular sentiment against the Mbeki government resulted in President Jacob Zuma winning the leadership of the ANC in 2007 and in the removal of Mbeki from office in 2008 (President Kgalema Motlanthe held office for a short period in the interim). Zuma won with the support of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and other groupings on the left inside the ANC. However, under his leadership, instead of a progressive economic policy agenda to engage with the country’s development challenges, an increasingly clientelistic political settlement emerged. This included vertical fragmentation of control within the ANC as extractive rents were competed over from local to national levels of government and in state-owned corporations.[40] The message was that the market economy was rigged against the majority and that the only way to accumulate was through leveraging state influence.

For a time, public-sector trade unions were kept onside by higher public wage settlements, while industrial unions fractured. The public-wage premium increased as did public sector employment, diverting funds away from such items as investment in public infrastructure, even as service delivery deteriorated and protests increased.[41]

The impact on industrial policy was profound, as conflictual stances were taken across government on a host of policy areas vital for industrialization. Levers such as local procurement were employed for short-term rent capture across government. As a result, there were missed opportunities for building local capabilities in a number of areas, including machinery component manufacturing from the Transnet procurement process.[42][43]

Zuma’s main strategy to gain leadership within the ANC was to divide the party so as to alienate Mbeki and his supporters. Once he was in power, it became important to bring in wider interests, reflected in a larger and more fragmented Cabinet. The number of ministries grew from 26 to 36. The proliferation of government departments made coordination of policy almost impossible.

The narrative of “white monopoly capital” was used by Zuma and his allies to remove internal political opponents, incuding ministers, and replace them with others, many of whom were to emerge later as having connections to the Gupta family associates linked to state capture.[44] Despite the rhetoric on ‘radical economic transformation’ and fighting South Africa’s triple challenges of high unemployment, inequality, and poverty, there were very few interventions to trigger structural change or address real impacts of monopoly power on the economy. The most significant was the black industrialist programme, involving financing by the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) and the DTIC, as well as public procurement, to address the challenges of access to markets.

The remaining industrial policy rents continued to flow towards established businesses. The incentive programme for the automotive industry was also updated, but it continued to disproportionately benefit the multinational OEMs and there was limited upgrading through linkages to the automotive industry. Import tariffs were introduced to support the struggling upstream steel industry at a significant cost to downstream industries.[45] Incentives to support recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, such as the Manufacturing Competitiveness Enhancement Programme, also flowed to established firms, often financing investments that would have taken place without it.[46]

While firms broadly maintained profit levels in this period, there was limited investment in expanded productive capacity in South Africa.[47] Business argued this was because of political uncertainty associated with Zuma’s presidency.

Zuma’s presidency has often been framed as the ‘nine wasted years’ or ‘the corrupt years’. The implication of this is that the removal of the ‘bad apples’, coupled with a return to the ‘good governance’ agenda would resolve South Africa’s problems. We argue that it was also South Africa’s historic failure to tackle entrenched interests and open up the economy to mobilize higher levels of investment in new productive businesses that contributed to the conditions that enabled the brazen clientelism, patronage, and corruption that characterized the Zuma presidency.[48]

Conclusion

Four key observations emerge from our analysis of specific periods of the post-apartheid political economy.

First, the state is not monolithic but rather an arena where conflicts between powerful groups take place. Our industry case studies show how different interests are able to shape economic policymaking and regulation in their favour.

Second, the constitutive power of international norms not necessarily associated with particular institutions can shape development outcomes.[49] The rationalizing of South African conglomerates, combined with the internationalization of businesses and a narrower focus on protecting profits, undermined longer-term productive investments in South Africa.

Third, inequality makes politics prone to populism, understood in economic terms as personalized leadership that addresses broad but unorganized discontent. The rise of Jacob Zuma was in response to the growing discontent with outcomes for the majority of South Africans.

And fourth, institutional analysis alone does not explain the paths of economic transformation. Post-apartheid South Africa has developed some world-class institutions, which on paper should have ensured a more inclusive transformation of the economy. However, the way institutions work in practice depends on the responses of the organizations operating under these institutions.[50] The state capture years have been indicative of how power also lies outside formal institutions. It indicates, too, the need to instead build new coalitions with a long-term interest in wider participation and productive investment.

References

Andreoni, A., Mondliwa, P., Roberts, S., & TREGENNA, F. (2021). Structural Transformation in South Africa: The Challenges of Inclusive Industrial Development in a Middle-Income Country.

Andreoni, A., Mondliwa, P., Roberts, S., & Tregenna, F. (2021). Framing structural transformation in South Africa and beyond. In Structural Transformation in South Africa: The Challenges of Inclusive Industrial Development in a Middle-Income Country,pp. 337-362. Oxford University Press, 2021.

Ashman, S., B. Fine, and S. Newman (2011). ‘The crisis in South Africa: neoliberalism, financialization and uneven and combined development.’ Social Register 47: 174–95.

Beare, M., Mondliwa, P., Robb, G. and Roberts, S. (2014). Report for the Plastics Conversion Industry Strategy. Research report prepared for the Department of Trade and Industry. Mimeo.

Bell, J., S. Goga, P. Mondliwa, and S. Roberts (2018). ‘Structural transformation in South Africa: moving towards a smart, open economy for all.’ CCRED Working Paper 9/2018. Johannesburg: CCRED.

BEE Commission (2001). Black Economic Empowerment Commission Report Johannesburg: Skotaville Press.

Bhorat, H., M. Buthelezi, I. Chipkin, S. Duma, L. Mondi, C. Peter, M. Qobo, M. Swilling, and H. Friedenstein (2017). ‘Betrayal of the promise: how South Africa is being stolen.’ State Capacity Research Project. [Online] Accessed https://pari.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Betrayal-of-the-Promise-25052017.pdf (accessed 09 April 2021).

Bhorat, H., K. Naidoo, M. Oosthuizen, and K. Pillay. (2016). ‘South Africa: demographic, employment, and wage trends.’ In H. Bhorat and F. Tarp (eds), Africa’s Lions: Growth Traps and Opportunities for Six African Economies, 229-270. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Black, A. and S. Roberts (2009). ‘The evolution and impact of industrial and competition policies.’ In J. Aron, B.Kahn, and G. Kingdon (eds), South African Economy Policy under Democracy, 211–43. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Black, A., Craig, S., & Dunne, P. (2016). Capital intensity, industrial policy and employment in the South African manufacturing sector. REDI3x3 Working paper 23. Cape Town: REDI 3X3.

Bosiu, T., Nhundu, N., Paelo, A., Thosago, M., & Vilakazi, T. (2017). Growth and Strategies of Large and Leading Firms-Top 50 Firms on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. CCRED Working Paper 17/2017. Johannesburg: CCRED.

Chabane, N., A. Goldstein, S. Roberts (2006). ‘The changing face and strategies of big business in South Africa: more than a decade of political democracy.’ Industrial and Corporate Change 15(3): 549–78.

Crompton, R. and L. Kaziboni (2020). ‘Lost opportunities? Barriers to entry and Transnet’s procurement of 1064 locomotives.’ In T. Vilakazi, S. Goga, and S. Roberts (eds), Opening the South African Economy: Barriers to Entry and Competition, 199-214. Cape Town: HSRC Press

Dallas, M.P., S. Ponte, and T.J. Sturgeon. (2019). ‘Power in global value chains.’ Review of International Political Economy 26 (4): 666–694.

Gray, H. (2018). Turbulence and Order in Economic Development: Institutions and Economic Transformation in Tanzania and Vietnam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gray, H. (2019). Understanding and deploying the political settlement framework in Africa. In N. Cheeseman, R. Abrahamsen, G. Khadiagala, P. Medie, & R. Riedl (Eds.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Politics Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.888

Gumede, W. M. (2007). Thabo Mbeki and the Battle for the Soul of the ANC. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Theobald, S., O. Tambo, P. Makuwerere, and C. Anthony. (2015). ‘The Value of BEE Deals.’ Report, Johannesburg: Intellidex.

Joffe A., Kaplan D. E., Kaplinsky R. and Lewis D. (1995) Improving Manufacturing Performance: The Report of the Industrial Strategy Project. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press.

Khan, M. H. (2018). ‘Power, pacts and political settlements: a reply to Tim Kelsall.’ African Affairs 117(469): 670–94.

Khan, M. H. and S. Blankenburg (2009) ‘The political economy of industrial policy in Latin America.’ In G. Dosi, M. Cimoli, and J. E. Stiglitz (eds), Industrial Policy and Development: The Political Economy of Capabilities Accumulation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Khan, M. H. and K. S. Jomo, eds (2000). Rents, Rent-Seeking and Economic Development: Theory and Evidence in Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, K. (2015). ‘Capability building and industrial diversification.’ In Jesus Felipe (ed.), Development and Modern Industrial Policy in Practice: Issues and Country Experience, 70–93. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Machaka, J. and S. Roberts (2003). ‘The DTI’s new “integrated manufacturing strategy?” Comparative industrial performance, linkages and technology.’ South African Journal of Economics 71(4): 679–704.

Macroeconomic Research Group (1993). ‘Making democracy work: a framework for macroeconomic policy in South Africa.’ A report to members of the Democratic Movement of South Africa. University of Western Cape, Centre for Development Studies.

Makhaya, G. and S. Roberts (2013). ‘Expectations and outcomes: considering competition and corporate power in South Africa under democracy.’ Review of African Political Economy 40(138): 556–71.

Mondliwa, P. and S. Roberts (2018). ‘Rewriting the rules governing the South African economy: a new political settlement for industrial development.’ Industrial Development Think Tank Policy Brief 10, Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development.

Mondliwa, P. and S. Roberts (2019). ‘From a developmental to a regulatory state? Sasol and the conundrum of continued state support.’ International Review of Applied Economics 33(1): 11–29.

Mondliwa, P. and S. Roberts (2020). ‘Black economic empowerment and barriers to entry.’ In T. Vilakazi, S. Goga,and S. Roberts (eds), Opening the South African Economy: Barriers to Entry and Competition, 215-230. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Mondliwa, P., S. Goga, and S. Roberts (2021). ‘Competition, productive capabilities and structural transformation in South Africa.’ European Journal of Development Research (2021), DOI:10.1057/s41287-020-00349-x.

OECD (2013). ‘OECD economic surveys: South Africa, Paris.’ Paris: OECD Publishing.

Padayachee, V., & Van Niekerk, R. (2019). Shadow of Liberation: contestation and compromise in the economic and social policy of the African National Congress, 1943-1996. Johannesburg:Wits University Press.

Ponte, S., S. Roberts, and L. van Sittert (2007). ‘“Black economic empowerment”, business and the state in South Africa.’ Development and Change 38(5): 933–55.

Public Protector (2016). ‘The state capture report.’ http://www.saflii.org/images/329756472-State-of-Capture.pdf(accessed 6 June 2020).

Roberts, S. (2000). The internationalisation of production, government policy and industrial development in South Africa. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Birkbeck (University of London).

Runciman, C. (2017). ‘South African social movements in the neoliberal age.’ In M. Paret, C. Runciman, and L. Sinwell (eds), Southern Resistance in Critical Perspective: The Politics of Protest in South Africa’s Contentious Democracy, 36–52. Abingdon: Routledge.

Rustomjee, Z (2013): 20 year review-economy & employment: Industrial policy.’

Input Paper for South African Presidency 20 Year Review, May 2013. Mimeo.

Rustomjee, Z., L. Kaziboni, and I. Steuart. (2018). Structural transformation along metals, machinery and equipment value chain—Developing capabilities in the metals and machinery segments. CCRED Working Paper 7/2018. Johannesburg: CCRED.

UNCTAD (2018). ‘Trade and development report.’ Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

World Bank (2018). ‘Overcoming poverty and inequality in South Africa: an assessment of drivers, constraints and opportunities.’ Washington, DC: World Bank.

Zalk, N. (2016). ‘Selling off the silver: The imperative for productive and jobs-rich investment: South Africa.’ New Agenda: South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy, 2016(63), 10-15.

Zingales, L. (2017). ‘Towards a political theory of the firm.’ Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(3): 113–30.

[1] This article is an edited extract from a chapter by the authors in: Structural Transformation in South Africa: The Challenges of Incluisve Industrial Development in a Middle-Income Country (eds: Andreoni, A; Mondliwa,P, Roberts, S, and Treganna,F), Oxford University Press, 2021(a)

[2] Andreoni, A., Mondliwa, P., Roberts, S., & Tregenna, F. (2021b). Framing structural transformation in South Africa and beyond. Structural Transformation in South Africa: The Challenges of Incluisve Industrial Development in a Middle-Income Country

[3] Andreoni et al, 2021

[4] Bell et al, 2018

[5] Khan and Jomo, 2000; Khan and Blankenberg, 2009; Gray, 2008

[6] Khan, 2018

[7] Gray, 2018

[8] Gray, 2019

[9] Khan, 2018

[10] Makhaya and Roberts, 2013

[11] Bell et al, 2018

[12] Andreoni et al (2021c) and Bell et al, 2021

[13] Sasol is the upstream supplier of chemical inputs including polymers used to produce plastic products.

[14] Mondliwa and Roberts, 2019

[15] This only counts the narrowly defined sub-sectors and not the related areas, such as automotive components classified under other sub-sectors, and agricultural production and packaging in the case of food.

[16] Barnes, Black, Monaco (2021)

[17] These are the main auto multinationals, which design and govern assembly of vehicles.

[18] This seemed to be changing, when in 2019 a process began for developing a master plan to support fruit alongside other selected agricultural products.

[19] Black and Roberts, 2009.

[20] Ashman et al, 2011

[21] The largest South African conglomerates, led by Anglo American and Richemont/Rembrandt (now Remgro) had always been internationalized, even while being identified as South African partly because of their origins and partly because of their response to economic sanctions during apartheid. However, these were still family-controlled conglomerate groups with a very substantial part of their business based in South Africa. Remgro has remained family-controlled and Anglo American has unbundled; the huge growth in foreign ownership was boosted by AB Inbev’s acquisition of SABMiller (the biggest listed company in recent years in terms of its market capitalization).

[22] Zingales, 2017, UNCTAD, 2018

[23] Iscor was the state-owned and vertically integrated steel producer with interests in iron ore and steel production. When it was privatized, it was split into Kumba Iron Ore and Arcelor Mittal South Africa.

[24] OECD, 2013; World Bank, 2018

[25] Padayachee and van Niekerk, 2019

[26] Roberts, 2000

[27] Mondliwa et al, 2020; Mondliwa et al, 2021

[28] Roberts, 2000

[29] MERG, 1993

[30] Gumede, 2007

[31] Machaka and Roberts, 2003

[32] Black et al, 2016; Mondliwa and Roberts, 2019

[33] Rustomjee, 2013

[34] Black and Roberts, 2009

[35] Bell et al, 2018

[36] Ponte et al, 2007; Mondliwa and Roberts, 2020

[37] BEE Commission, 2001; Mondliwa and Roberts, 2020

[38] Intellidex, 2015

[39] Runciman, 2017

[40] Makhaya and Roberts, 2013; Public Protector, 2016; Bhorat et al, 2017

[41] Bhorat et al, 2016; Runciman, 2017

[42] Crompton and Kaziboni, 2020

[43] Transnet is the state-owned monopoly in rail, ports, and pipelines. In 2012, Transnet embarked on its largest-ever single order of 1,064 locomotives with local content requirements. However, the project was later found to be corrupt and the local-content requirements were bypassed in a number of instances.

[44] Bhorat e al. 2017

[45] Rustomjee et al, 2018

[46] Beare et al, 2014

[47] Bosiu et al, 2017

[48] Zalk, 2016; Mondliwa and Roberts, 2018.

[49] Dallas et al, 2019

[50] Gray, 2018

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.